Ephemeral Light

Date: October 2021 - March 2024

Platforms: PC, Consoles

Role: Project Director

Genre: RPG

Concept

Project Ephemeral Light had a wide variety of influences and inspirations. I wanted to create something that matched my own strengths and passions. As such I wanted to make both a narrative-driven game that was heavy on companionship and character relations, and also a game that had deep mechanical systems of interaction and gameplay. The natural result was thus to make a tactical RPG.

The game had 3 design layers. These were:

-

Narrative: which was to be primarily delivered through dialogue, prose, visual design, and environmental storytelling.

-

Combat: which is where the core gameplay will mostly be and the player can play a tactical game.

-

Metagame: where the player collects and upgrades their party over time, building up a team of companions.

The structure of the game was to be broken down into 3 main acts and an interlude act. The first act centered around the story of fleeing the city of Vatan and had a mostly linear structure.

Meanwhile the second act involved the characters starting a new life while struggling against their newfound neighbors, and ends with the protagonist discovering they’re a shapeshifter and bonding with their metamorph. Act 2 was a more open act, where the player could choose what to do in a given day and included a narrative-driven roguelite mode where the protagonist would enter the world of dreams and fight against a corrupting force. A calendar would track the progress of the player, and on certain days, a prescripted main story mission would trigger similar to act 1. Act 2 also includes the bulk of the companion missions: select missions unique to each companion.

Act 3 was to be a short finale where the shapeshifters try to take back their home city of Vatan from the ruling captain of the order.

Core Themes

The primary themes of Ephemeral Light was to be about 3 things:

-

Self-discovery and finding one’s purpose.

-

Oppression as a marginalized minority, and how there are different ways to respond, whether that’s assimilation, absconding, solidarity, or retaliating.

-

Imperialism, its effects on destabilizing lesser nations, and how the powers that be can be in alignment with each other even when publicly and explicitly opposing one another.

These were chosen based on the author’s lived experiences and domains of personal interest, where I felt I had a unique voice with something meaningful to contribute.

With these design layers, and themes we wanted to deliver, we could then move onto building the narrative and systems of the game. But before that, the game’s design pillars had to be chosen according to these needs.

Design Pillars

Design pillars are core principles chosen for a game’s design that guide and constrain all major and minor creative decisions. Four design pillars were chosen for the game using a rationalist ab initio reasoning method to hone in on exactly what kind of game design and emotional aesthetics we were aiming for. These four pillars were:

-

Design *For* Emergence, Not Emergence Itself

-

Avoid Player Calculation, Make Player Moves Intuitive

-

Make it Relatable

-

Make it Hard and Deep

I documented the design pillars in detail, the reasoning for each, and examples of each in a design document. Due to the method used, this was a relatively heavy on theory document. It can be viewed in full here.

Combat

The goal of the combat was for it to be something that was mechanically deep and challenging, without being solvable through calculations. The combat was to be turn-based on a hexagonal grid where players controlled a select few characters.

Multiple iterations were made during the development of the game based on feedback from playtests and design discussions within the team. Initially the game was structured in a rube goldberg machine manner, where players would input 2 command moves in advance for each of their units, and then would press the “Ready” button which would then simulate the turn, one action at a time.

Concept art of an early prototype of the combat featuring the 2 commands per unit ordering system.

However after extensive playtests we decided to scrap this version of the combat as it was too confusing for players, especially with the existence of conditional abilities that would further complicate predictability. Therefore after multiple iterations, we settled on a version that would remove the pre-ordering of input commands, and instead use a conditional-turn-based system common in many JRPGs. In this new system, units “move” through a timeline based on their speed stat, and when they reach the end, it becomes their turn. Then depending on what ability they used and what “delay” stat the action had, they will then move backwards in the timeline. We also introduced a poise bar to units that become depleted with stagger. Once a unit’s poise is depleted they are stunned and paralyzed, which knocks them all the way down on the timeline and freezes them there for one turn.

Concept art of a later prototype of the combat featuring the timeline and change of conditional abilities

Conditional abilities would also show up as part of the HUD when they are ordered by any unit. You can see some of the combat in the final version below in action, that includes flanking attacks, the stagger/poise system, and the timeline structure:

Final version of the combat system that was implemented!

Abilities

For abilities, the game drew a lot of inspiration from MOBAs, but implemented in a turn based structure. Similar to MOBAs, each unit has an ultimate, and a number of unique abilities in addition to basic attacks. I designed all of the abilities for the units, including for bosses and enemy goons. The design of these abilities were done in accordance with the design pillars, particularly the first two. Abilities were designed to be simple but with emergent possibilities in their utilities in game.

An example of abilities for 2 units.

Narrative

Characters and their relations were to be the backbone of the game’s narrative. However that didn’t mean we were going to shy away from creating a rich world with deep backstories and lore, and intertwined plots full of twists and turns. I approached the narrative design of Ephemeral Light using a top-down approach, where I would start from character sheets and high level lore and plot structure.

Then one layer deeper I would construct the missions and their main plot beats and events. And then finally there was writing out the individual missions, including every line of dialogue and player choice. Here is an example of a script for one of the shorter and latter missions of Act 1.

As an RPG we wanted to give players some forms of agency, but like many great narrative-driven RPGs, we also wanted control over the story and its direction to give a hand-crafted experience. This meant that player choices had to exist, but also be controllable. The narrative system we used was the tried and tested beads-on-a-string branching system where most player choices eventually, and usually (but not always) very quickly, would reconnect to the main branch.

The Hub was the resting area between missions where the player could talk with companions.

Between missions, players would enjoy the safety of the hub area, which depending on the point in the game’s story would change a couple of times. In the hub area, players could talk to their companions. Talking to companions, and the choices you made in those conversations, would branch out further in the game and could potentially lead to losing those companions or gaining new ones.

One core design choice was to make sure that the companions were living people with their own agency, and not just reactive puppets that the player can manipulate. That meant that there was no single correct way for the player to approach the companions for metagame purposes.

Companions had their own love interests, character goals, and conflicts. One companion might leave if you encourage them to pursue a personal goal, while another might leave if you don’t try to help them overcome their personal insecurities.

.png)

Talking to companions in the hub.

During most of pre-production the narrative was to be primarily delivered through a visual novel system as a means to save on production costs. However by the end of pre-production we felt that it would be very valuable to add an exploration mode where the player can control their character to move around in.

This achieved a stronger sense of immersion and liveliness with the world. It also allowed for opportunities of environmental storytelling and lore drips. The visual novel system was still used for delivering dialogue scenes within the exploration mode, and it was still utilized for scenes that can give the player an easier and more detailed sense of place such as in indoor scenes.

An example of the exploration mode in the demo.

The story of Ephemeral Light is focused on the protagonist Harsin, an officer in the order of neutralizers, tasked with hunting down shapeshifters. After learning that his friends are shapeshifters, he decides to help them flee from the oppressive the city-state of Vatan to safe lands. While there are epic world-changing events happening during the story, the focus of the player’s POV is on a much smaller scale, and is about the adventure of Harsin and his companions. However through clashes with high-ranking powerful characters and through flashbacks in dreams, the story of the world and its major political players is also told, as the audience puts together the pieces.

.png)

The lore in the journal hinting at a rich history that the player can piece together.

The journal also serves as the lore reference point for the player as they progress through the story and unlock new pages. Countries, organizations, characters, and historical events all get their own entries in the “History” tab of the Journal.

.png)

.png)

More examples from the journal.

Metagame and Progression

No RPG is complete without a progression system. I designed the progression system for the game. Among the decisions to make was on how to handle companions that the player doesn’t play with. Since a lot of missions included mandatory companions, I needed to make sure that all companions were viable at all times.

Using some excel math, I decided to include 2 forms of XP gain. One would be a party-wide award for completing a combat scenario given to all participating companions in a given combat scenario, and another would be a full equal XP reward to all companions at the conclusion of certain checkpoints such as completing a story mission.

The Leveling curve, alongside the minimum that would be shared.

By tinkering with the ratio between these two variables, we can know how much a hypothetical farthest behind character can be in terms of XP as a matter of percentage. With that percentage we can use a simple exponential progression curve for XP required to level up, and then match the growth percentage with the percentage of XP shared to everyone to fix how far a character can possibly fall behind in terms of levels. Using this method I pinned the farthest behind character at a maximum of 2 levels (characters start from level 1 and go up to a maximum of level 25).

Finally I went through each individual level’s XP requirement, and adjusted values. This was specifically done for the second act of the game where the RPG aspects of the game open up to the player more. We wanted to give the player a stronger sense of agency, and therefore we allowed a higher degree of deviation, with the maximum possible level difference increasing to 5 levels. However, the values have also been adjusted so that XP requirements rise up substantially towards the end of Act 2, which would then further incentivize players to get their companions who were behind to catch up.

.png)

The character's screen, where they could level up their skill tree.

The rewards for leveling included a flat attribute increase across all 4 primary stats (HP, Def, Off, Speed), and an additional increase to the character’s “main attribute” that was highlighted in green, which varied by character and are fixed to reflect the playstyle and role of that character. In addition to the attribute increases, every level grants a character a skill point that could be consumed to unlock a new space along their skill tree.

The skill tree included new abilities, ability upgrades, and a selectable attribute boost, wherein the player can choose which attribute to increase. This was to create a greater sense of player agency and possession towards their playthrough and party.

Additional Progression Features

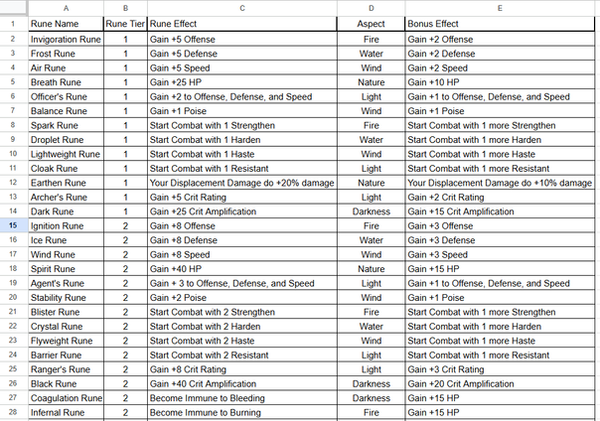

Further progression features were designed that didn’t see implementation before the project was canceled. These included the inventory system, the rune system, and the consumable system. Runes were to be effectively equipment that could be equipped to characters that bestowed them additional attributes or passive abilities. Consumables were permanent upgrades that could further boost characters, but these were limited by how many times a player could give a certain consumable to each individual character.

During Act 2, the player could play a roguelite mode that would grant them additional rewards and chances to level up their characters. It also included a “hunt” mode, where the player could send off companions away for a given calendar day, and they would then return with random rewards, and additional XP gained for the companions on the hunt.

The preliminary design of the runes. Runes that were given to characters of their matching Aspect would gain bonus effects.

Preliminary concept art for the inventory system.

Technical Production

During the game’s production, through collaboration with our engineers I helped design multiple tools to aid in the production of design assets and drastically increase productivity and implementation time for designers. The main two of these were the combat level editor, and the narrative editor tool. You can see more of the narrative editor tool in this video made by my former colleague.

The Narrative Editor

Below is an example of the combat level editor:

The Combat Level Editor

Bringing The World to Life

As the project director I collaborated closely with our lead concept artist and music composer to bring the world to life. Every character and every setting were meticulously crafted to bring forth the vision for the game and story.

Concept art of Lilac, one of the primary antagonists and final boss of the game.

Environmental concept art for VN scenes, that were to be used as reference for the exploration mode

In addition to creating various music songs for different narrative moments and occasions, every companion and primary antagonist had their own theme song that reflected their character and role and vibe in the story. Here are some select tracks from the game's soundtrack.